Magazine

Changing Demographics and the Agile College

Spring 2022

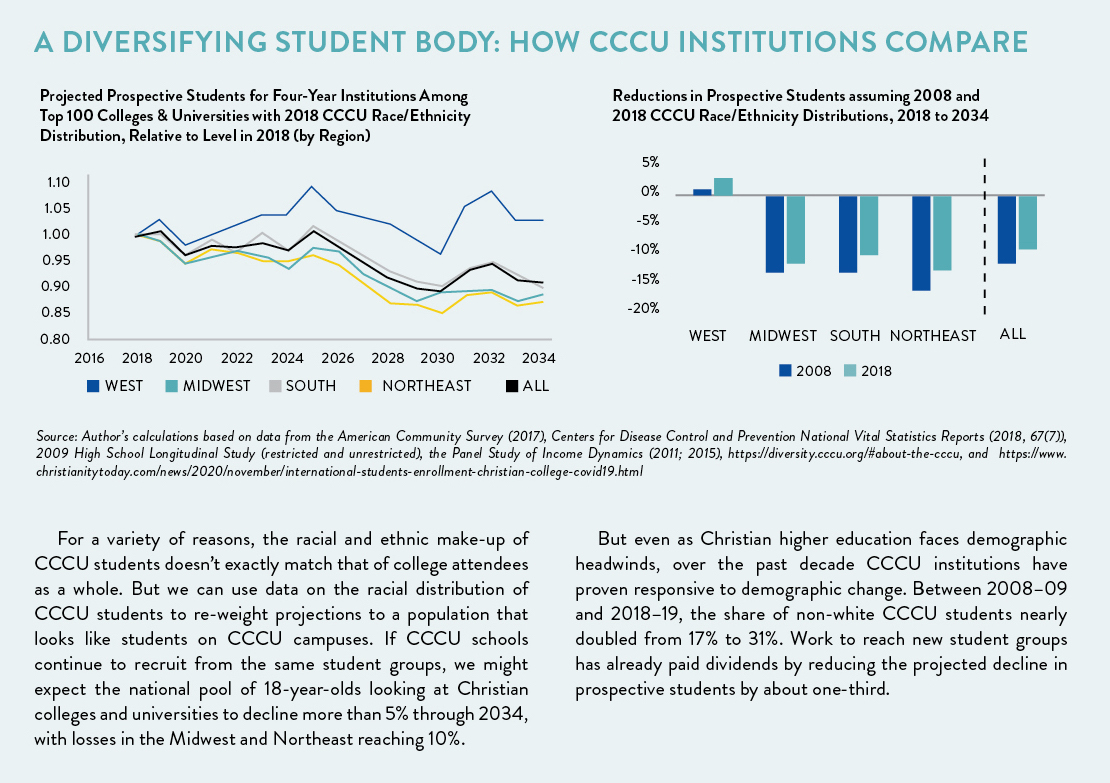

Nathan D. Grawe

The CCCU is committed to assisting institutions in addressing and engaging the current issues of the day. At the 2022 International Forum, Nathan D. Grawe, professor of economics at Carleton College and author of Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education and The Agile College, gave a plenary session addressing the coming demographic changes for higher education broadly and CCCU institutions specifically. We asked him to adapt content from that session that is most relevant for CCCU institutions into an article. The most relevant data he selected is pictured throughout the article; the body includes his insights and suggestions for responding to the data.

I recently read a Washington Post article on higher education in which the author referred to the upcoming demographic changes among our student populations as “the apocalypse.” I don’t like that metaphor on several levels. It doesn’t seem theologically sound, but it also isn’t practically helpful to people leading colleges and universities. If what lies ahead is the apocalypse, we should just throw in the towel, go home, and be with loved ones.

Thankfully, higher education has far more agency than this metaphor suggests. Institutions already grappling with demographic change offer ideas for proactive response. Demographic change is real, but we can adapt.

Redoubling Access Efforts

As prospective student pools shrink, I expect continued urgency around the access agenda. For many of us, that means holistic admissions. While some implement this approach through test optionality, others pursue similar goals while retaining test requirements. For example, the College Board’s Landscape tool contextualizes student test scores with statistics about the student’s home community — poverty rates, education levels, home ownership rates, and the like. Community characteristics are summarized in an index capturing the degree of adversity faced by the student. When Landscape users consider students with a particular test score, their evaluation can be influenced by whether a student earned that score with all of the advantages one could imagine, or by overcoming significant adversity.

The Landscape tool has been applied productively by institutions as diverse as Wellesley College and Florida State University. When testing the tool, the latter used it in the context of admission to a summer bridge program. The admissions team was so happy with the result that they decided to reconsider applicants in their regular admissions process who faced high adversity and were slated for likely rejection. After rereading those files with the environmental context in mind, the admissions team identified more than 1,000 additional admits, resulting in 400 additional matriculations. This experience reminds us that when we incorporate greater context — however we do that — we may come to a different conclusion about whether a given student has what it takes to be successful at our institutions.

Serious efforts to expand access will require something of us. I offer an example from Drake University not because we should all follow this specific strategy, but rather because it demonstrates an important attitude. The university identified a subgroup of unserved prospective students. This group didn’t fit Drake’s four-year profile because it seemed they would have a better experience beginning with a two-year program. In response, Drake decided to expand its program offerings to include a two-year degree. I admire this decision because it shows an openness to potentially radical change — to reconsidering even the institution’s self-identity. Too often we implicitly say to students, “You need to adapt and meet us where we are at,” when instead we need to be asking, “How must we change to be ready for the next generation of our students?”

In my work as a professor, I have been thinking about these questions in the context of my own classroom. The George Floyd murder occurred just an hour from my home. So, not surprisingly, my church, like many others, prayerfully considered how God calls our body to respond. I was on our church council at the time and began studying others’ work on racial reconciliation. A sermon from the McLean Bible Church in Virginia grabbed my attention. It began with short reflections by people of color in their congregation. While they were generally positive, several congregants spoke of feeling “welcomed” with a bittersweet tone. “Welcome” implies something like, “This is your space and I’m allowed to be in it, but it isn’t my home.”

The sermon went on to unpack Psalm 133, a psalm of ascents that would have been sung when God’s people came together. Such a time of gathering would surely highlight distinctions between the tribes. The psalm begins, “Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.” The word “good” in this verse is apparently the same word used repeatedly in Genesis 1. God created and it was good — Eden good. The pastor underscored that what is good, according to the psalm, is when we live together in unity, not in uniformity.

The sermon convicted me and has caused me to think about my classroom and my prior aspiration to create a welcoming environment. I believe that was the wrong aspiration. While I am ultimately responsible for the classroom environment and so must take ownership on that level, my goal is that all students feel ownership over the space, free to be who God intended them to be — and that none would conclude, “That’s someone else’s class, though I’m welcome there.”

This is the shift of mentality that I see Drake grappling with: the willingness to change and even sacrifice to create a space that becomes home to somebody else.

Focus on Retention

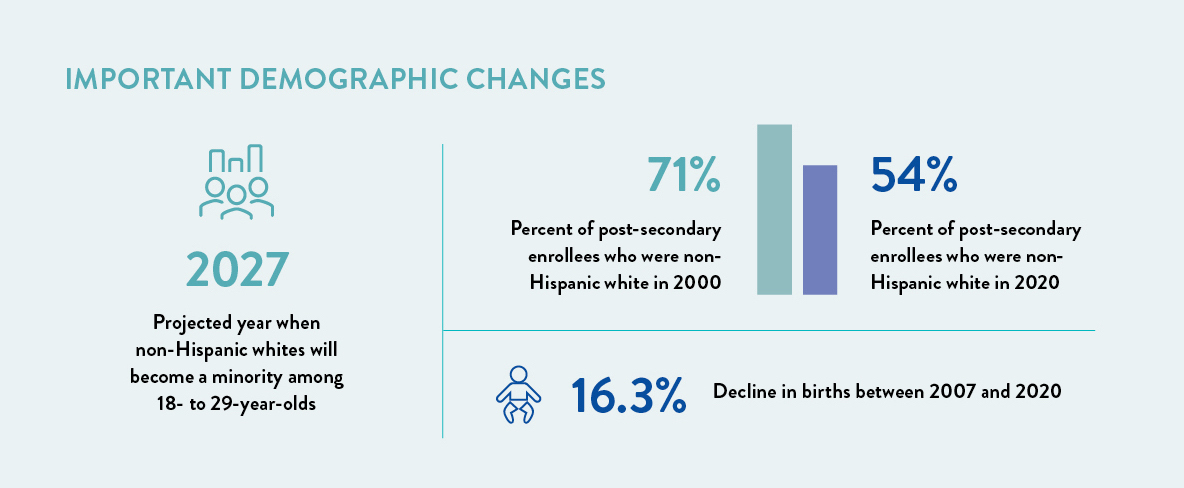

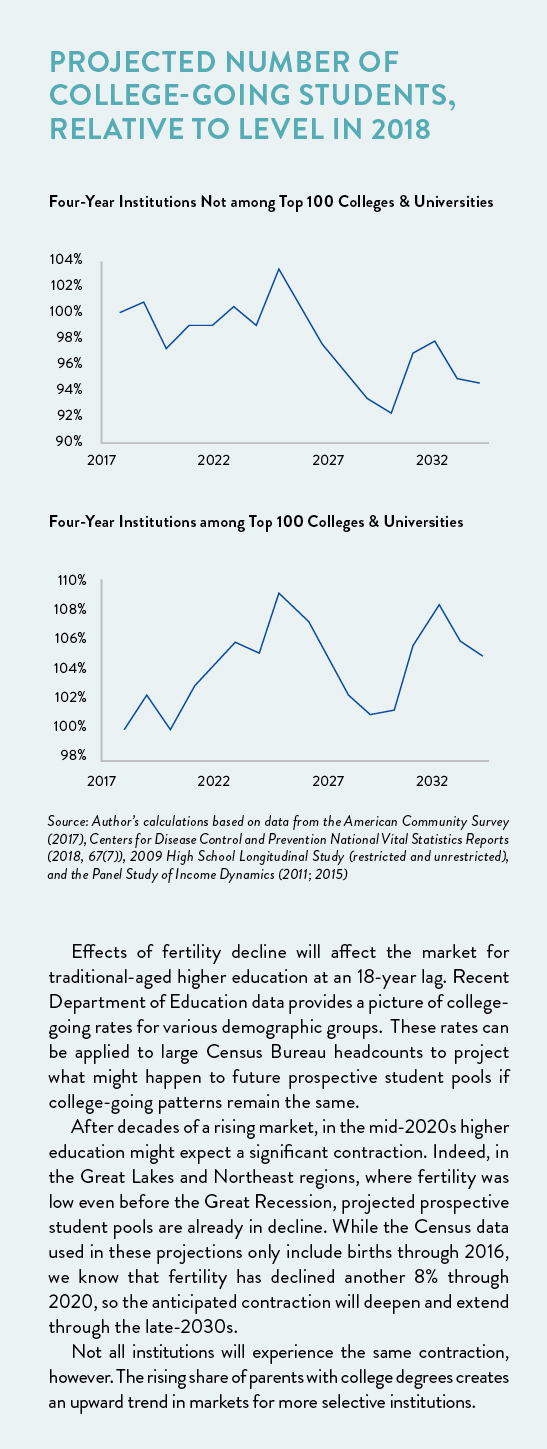

With a 16% decline in the number of babies being born over a short period of time, it is not realistic to expect that higher education will recruit its way out of demographic contraction. Admissions staff need to be on the top of their game, to be sure. But if our only response is to recruit harder, we’re going to come up short. We do, however, have a second lever for increasing enrollment: retention initiatives. Even partially addressing long-standing issues of student attrition would largely eliminate enrollment challenges for many campuses over the next 15 to 20 years.

Retention work takes many forms. Saint Cloud State University surveys students in the fall term of the first year. After just three weeks, they can identify students who, despite having a B average or better, will have a 20% attrition rate into spring term due to a low sense of social belonging. By identifying at-risk students early, the university can coordinate with faculty and staff to connect with those students before it is too late.

Another example: Rutgers University creatively turned student employment into an on-ramp for academic support. They’re training supervisors in the library, gym, and student center to be mentors, conduct weekly check-ins, and make referrals to academic support as necessary.

Retention programs that engage faculty and staff across the campus will be essential to significant improvements in student success. As important as the office of enrollment management may be, it is too small to sustain progress working alone. Each faculty and staff member engages students in a variety of contexts, and each of these interactions represents an opportunity to invite those students to re-enroll or to walk away. Until all parts of the campus recognize our shared responsibility for retention and student success, we’re going to struggle.

At Wheaton College in Massachusetts, former president Dennis Hanno argued that the institution could not be a national leader in liberal arts education while not retaining at least 90% of its first-year students. To communicate the shared responsibility for this outcome, the college put a bounty on the first-year retention rate: When they reach the goal, everyone on campus will get a raise.

An incentive like that articulates clearly the importance of retention, both to the financial bottom line and to the institution’s mission. To put it more personally: Every time a student walks away from my campus at Carleton, it’s a mini tragedy. I can no longer view such tragedies as an acceptable cost of doing business. For each one of those students, something really unhappy happened, and it’s my job to do what I can to keep that from happening.

New Connections Inside the Institution and Beyond

It is difficult to believe that colleges and universities can reach new students or retain them longer without making changes to the curriculum. Sometimes this can involve synergistic use of existing courses. For example, Wheaton College in Illinois recently developed the cohort-based Aequitas Program in Urban Leadership. Research suggests that cohort programs can contribute to student success. In addition, the program’s urban leadership focus may speak to new student groups and so serve recruitment goals. While the program does involve some new elements, many courses were pre-existing.

Other programs may pursue greater retention by making a stronger connection between what students are doing in their studies and life after college. Research by Gallup and Strada finds that students who see a connection between coursework and life after college are more likely to say that their educations were of high value and worth the cost. Emphasizing such relevance makes some think immediately of business and STEM fields. But I want to stress that all departments and programs can emphasize relevance. For example, Scripps College, a leader in the humanities, has developed a senior capstone experience in which humanities students address problems like environmental degradation or homelessness from a uniquely humanistic lens. The experience helps students to articulate for themselves — and later to employers — how a deep understanding of what it is to be human provides a great foundation for solving many problems we face today.

Some responses to demographic change will involve merging or partnering with another institution. The Transformational Partnerships Fund, led by SeaChange Capital Partners and the ECMC Foundation, offers grants to institutions that see a path forward involving deep collaboration. Even when a new partnership provides great benefits, transitioning to the new relationship involves costs. And institutions seeking such transformation often lack resources. A grant from the Fund can bridge this gap.

The COVID Impact

Obviously, many colleges have experienced real enrollment challenges due to the pandemic. While overall enrollments were down across all sectors, the enrollment decline was even greater among first-time enrollers. The National Student Clearing House Research Center noted a 6.3% decline in first-time enrollments among students at private nonprofit four-year campuses between fall 2019 and fall 2020; public two-year institutions saw a contraction of 18.2%.

Declines were especially pronounced among first-generation and low-income students. That’s not good news if we think that we’re going to address falling birth rates by expanding access. Those student groups who are most marginalized in the context of COVID are exactly the groups with whom we seek better and closer relationships. COVID has amplified the challenge.

To understand the problem COVID may have created, it’s worth looking back to the experience following the Great Recession. In the years leading up to 2009, the college matriculation rate among African American high school graduates quickly converged on the national average. Higher education was making great progress on the achievement gap. And then the financial crisis hit. Unemployment went up for all groups but disproportionately affected African American households. As a result, it wasn’t terribly surprising to see a downward blip in matriculation rates in that community. But today a decade of data shows that this was no blip — it was the start of a trend that reopened gaps. This experience from a decade ago is a reminder that as we face the present COVID challenge, we can’t allow a temporary pandemic to produce permanent enrollment losses.

International student enrollments have also been hampered by pandemic-era restrictions. According to the Institute of International Education, from 2019–20 through 2020–21 international student enrollments fell by 16%. As dire as that number may be, this figure underestimates the pandemic’s damage: In the same year, first-time international enrollments fell by over 40%, and in-person enrollment by first time international students fell 72%. While international student enrollment numbers in fall 2020 were tough enough, the larger picture may be dimmer still as it seems likely that we’ll see lower retention of this cohort due to distance education. In years to come, we will learn how the pandemic experience affected our relationship with international student communities and whether COVID limited one potential response to a weakening domestic market.

Hope for Tomorrow

As much as COVID has challenged us, the past two years may also prepare us for our future. In particular, the pandemic retaught us many important lessons. Here are just a few.

- Effective teaching and learning is student-centered. In the spring of 2020, students met with advisors to decide whether to return to campus the following fall. In that moment, the stakes were palpably high. Congressional bailouts were still uncertain, and the potential for a catastrophic decline in enrollment was all too real. Those advising meetings turned intensely personal as faculty and staff worked to understand just what would be necessary to allow each student to re-enroll. That experience can foster an appreciation of the power of deeply personal learning relationships and can provide a useful starting point for many initiatives designed to respond to shrinking student pools.

- A powerful residential education is more than a rental contract. In 2020–21, like many others, my home institution saw most students return. However, campus life was anything but normal. Many classes remained online, and our residential life program was severely limited by pandemic precautions. In too many ways, students experienced the college more as a landlord than as a curator of a rich residential learning community. As we come out of COVID, we have an opportunity to learn from that loss. What did we really miss when it was taken away? What elements of the residential experience showed themselves to be particularly critical by the pain we felt in their absence? In years to come, the answers to these questions should guide our investments as we create a vibrant learning environment.

- Retention is a holistic problem with holistic solutions. Distance learning in the pandemic offered many faculty members a digital window into students’ homes, and with that experience came rich learning opportunities. For example, in my office hours, I saw that what originally presented as a “math problem” may actually have reflected differences in social or financial capital. From these experiences, faculty have learned what the literature tells us — that retention is a holistic problem requiring holistic solutions. This recognition is a great foundation for work ahead to address declining student numbers with retention initiatives.

- Higher education is agile. All of those jokes about how sclerotic we are — jokes that many of us in higher education even tell ourselves — are untrue. As we depart pandemic-era education, we should take hold of our agile identity as we adapt to meet demographic change. At the same time, we must also recognize that some colleagues have experienced change fatigue, and more than a few institutions were strained by the process of pandemic decision-making. As we take on the mantle of agility, we also need to lean into relationships of shared governance, seeking reconciliation where needed.

A Non-Apocalyptic Metaphor

In a blog post, Ed Venit of EAB once pointed to a metaphor for higher education’s challenges with demographic change, one that is significantly more useful than “the Apocalypse”: the antifragile system described by Nassim Nicolas Taleb in his book Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder. Taleb notes that there are three responses to stress. We usually think of two of them. We know we don’t want to be fragile: I’m put under stress and I break. As we run from the broken transformation of fragility, we often aspire to resilience or robustness. Like a turtle, we are tempted to hunker down in our shell and let the stress pass over us leaving us unchanged. But there is a third, more positive response: antifragility. The antifragile system embraces stress-induced change and actually becomes stronger. For example, my skeletal, muscular, and cardiovascular systems all become stronger when I step onto a treadmill.

If we take the antifragile view of what higher education is experiencing right now — frankly, whether we’re confronting COVID or demographic change — a different picture emerges. In 2045, I don’t hope that we’ll look back and say, “Wow! That was fun.” There are going to be difficult choices, and we’re going to have to change, and that’s hard. But I do hope we can look back and see that we’ve expanded access, made greater connection between the work students do on campus and the lives of meaning that they will lead after they graduate, and increased rates of retention and student success. If we do reach that point, while the process of getting there will not necessarily have been fun, it may well have been worthwhile. We might yet rejoice and conclude that we are better fulfilling our missions so that we can continue to serve students and, in your case, serve God and his kingdom for decades to come.

Data Referenced in this Article Includes:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Various years. National Vital Statistics Reports.

- Council for Christian Colleges & Universities. “CCCU Campus Diversity Statistics.” 2021.

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics, public use dataset. Produced and distributed by the Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. 2019.

- Ruggles, Steven J., Sarah Floor, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek. 2019. IPUMS USA: Version 9.0 American Community Survey. Minneapolis: IPUMS.

- United States Census Bureau. “Summary File.” 2017 American Community Survey. U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Office, 2019.

- S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09), “Base Year, 2009.”

- S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09), “First Follow-up, 2009.”

- S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09), “Second Follow-up, 2016.”