Magazine

Fairness for All

Spring 2017

Shapri D. LoMaglio

The CCCU has been exploring a legislative initiative sometimes called Fairness for All. This initiative seeks to find a way to simultaneously combine federal protections for religious freedom and for LGBTQ persons, two “sides” that have often viewed their protections as being violated by the existence of protections for the other. Specifically, Fairness for All would create legal protections for LGBTQ persons in the basic areas of public space (employment, housing, stores, and restaurants), financial services, and jury duty service, while at the same time explicitly adding to the law the full scope of religious rights ensured by the Constitution.

Recent Federal History

The CCCU’s involvement now comes after four decades of debate about whether LGBTQ Americans should have expanded rights under the law. The Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) was the LGBTQ community’s primary federal legislative effort. ENDA would have prohibited employers from making hiring decisions based on an employee’s sexual orientation (later versions also included gender identity), but would have continued to allow religious employers to hire consistent with their religious beliefs. ENDA was first introduced in 1974 and was reintroduced in every session of Congress from 1994 to 2015. It passed in the House in 2007 and the Senate in 2013, but never became law. With each version, religious freedom advocates – myself included – had to work to ensure the religious exemptions remained strong despite offering no support for the base bill.

Less than a year after ENDA passed the Senate in 2013, the Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling in the Hobby Lobby case that affirmed the religious freedoms of for-profit business owners. While the CCCU supported Hobby Lobby and believes its case was correctly decided (theFirst Amendment makes no distinction between the rights of for-profit and nonprofit entities), the ruling alarmed many civil rights advocates as an affront to equal rights and changed the legislative landscape for religious exemptions. Long-standing religious exemptions like that in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which has allowed religious employers to consider religion in hiring largely without controversy since its passage in 1964, were suddenly seen as too expansive and, to some, dangerous.

Religious exemptions previously had wide bipartisan support; the Religious Freedom Restoration Act that provided the Supreme Court’s basis for a favorable outcome in the Hobby Lobby case was originally sponsored by Senator Chuck Schumer (now the U.S. Senate minority leader), passed by a Democratic Congress, and signed by President Bill Clinton. But in the wake of Hobby Lobby, religious exemptions were rejected by many on the left, specifically by many in the LGBTQ rights and women’s rights groups. The scope of what they viewed as acceptable religious exemptions had narrowed significantly.

The debate became even more polarized in the 114th Congress (2015-2016), during which time the landmark Obergefell case legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. Instead of reintroducing ENDA, some LGBTQ rights advocates introduced the Equality Act, which would have added sexual orientation and gender identity to almost every section of the Civil Rights Act without adding any new religious exemptions to resolve the inevitable conflict this would have created for religious organizations. In fact, the Equality Act would have rolled back some religious exemptions currently in law and would have explicitly prevented the application of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act to any of the inevitable legal conflicts.

The First Amendment Defense Act (FADA) was also introduced, which would have ensured the federal government and other federal agencies could not take negative action against people or organizations that defined marriage as between one man and one woman. While FADA’s intent was worthy, neither FADA nor the Equality Act resolved many of the nuanced questions of how expanded rights for LGBTQ Americans could intersect peaceably with First Amendment protections for religious individuals and institutions. Both FADA and the Equality Act have been labeled “winner-take-all” pieces of legislation.

State Activity

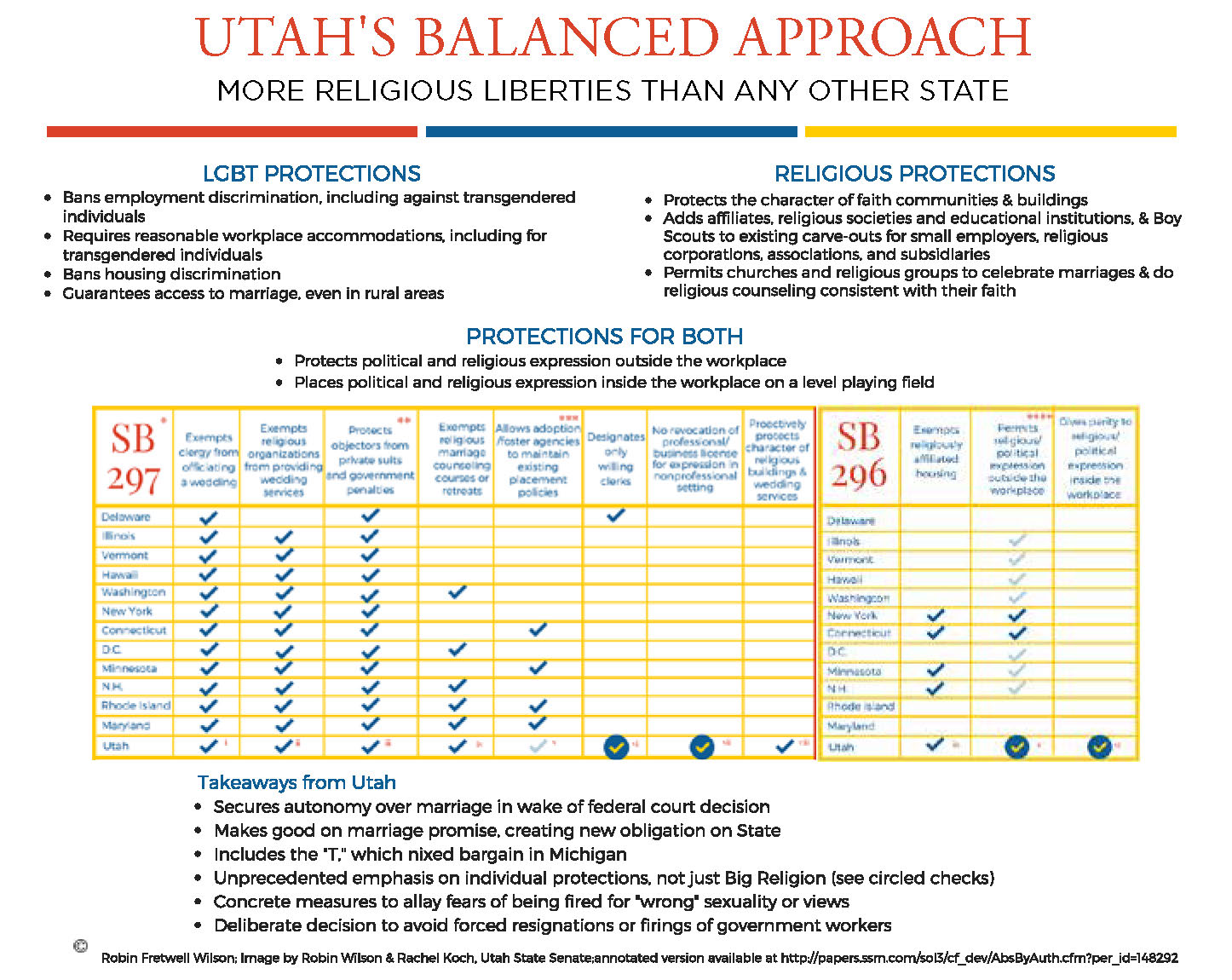

While these actions were occurring at the federal level, a parallel track of activity was transpiring at the state level. In early 2015, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and LGBTQ advocates supported a piece of legislation in Utah that addressed the concerns of LGBTQ Utahans while also strengthening constitutionally based religious protections.

Only three weeks after Utah passed that legislation, Indiana’s attempt to expand religious protections for business owners in the state without offering any protections for LGBTQ individuals created a national outcry. Many viewed it as an overreach; concerts and events were cancelled, leaders in multiple industries spoke out against the bill, and Indiana-based companies and organizations like the NCAA, Eli Lilly, and Angie’s List, among many others, threatened to leave the state. Eventually a “fix” was passed that many religious freedom experts think actually weakened religious freedom law in Indiana compared to before the episode.

There have been numerous overreaches in the other direction as well. Last year, California’s state legislature attempted to significantly undermine religious-based policies and practices of the state’s faith-based schools. Illinois and Massachusetts have effectively shuttered Catholic adoption agencies there by removing their ability to process only those adoptions consistent with their religious convictions about marriage. And in Iowa and Massachusetts, state officials attempted to prevent churches from operating according to their religious convictions by deeming them public accommodations simply because they hosted spaghetti dinners and other similar functions that were open to the public.

One thing has become increasingly apparent over the past few years: When LGBTQ protections go up against religious freedom, LGBTQ protections usually win in both the court of law and the court of public opinion. The only exception happened when the LGBTQ community and the faith community in Utah came together to find a way forward that protected the rights of each.

So is there a way forward nationally? Is it possible to get out of the winner-take-all paradigm we’ve been stuck in and secure rights for one group without doing so at the expense of the other? Can our law respect and create space for people who think and live differently than one another? We think Fairness for All may be the solution.

What Is Fairness for All?

Fairness for All is a legislative construct that would ensure that LGBTQ Americans cannot be denied access to employment, housing, financial credit, social service programs funded by federal money, service in business establishments, or jury duty service simply because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. But it would also ensure that churches and religious organizations that define marriage or gender differently than the United States government will not be found to be engaging in discriminatory actions simply because of their religious beliefs.

The general idea behind Fairness for All is that religious organizations can continue to hire employees and retain internal organizational policies that reflect their religious beliefs; additionally, they would not be treated differently by the government (e.g., denied government funding or tax-exempt status) because of their views on marriage or gender. In secular employment contexts, an employee’s religious beliefs would be respected by their employer unless it puts an unreasonable burden on the employer. Businesses would have expressive speech protections for political or religious speech. For example, a t-shirt printing company can neither be forced to print “Eat more beef” shirts if they are vegetarian, nor “I love Jesus” shirts if they are Buddhists.

One of the key misunderstandings that has shaped all of the events leading to this point is a broad cultural failure to recognize that civil rights are actually a balancing test. Rights for one person are always balanced against the rights of others. For instance, while we have the right to free speech, we cannot shout, “Fire!” in a movie theater or play loud music in the streets at midnight. Our right to free speech are subject to time, place, and manner restrictions. Thus, civil rights are best crafted with a scalpel, not an axe.

The CCCU, alongside other religious groups, is exploring the Fairness for All approach because we think it is an approach that uses a scalpel, not an axe. We believe that if the right balance can be struck, Fairness for All could preserve more freedom for more Americans into the future. We see this as a God-honoring pursuit in the pluralistic society we live in – a pursuit that protects religious freedom for all, including our members, while acknowledging and respecting the human dignity of all people, even if we disagree.

While many in our country are deeply religious, we are not a theocracy, and therefore we must find a legislative path that allows each person to live according to their beliefs and convictions. Fairness for All seeks to protect legislatively both those whose religious convictions about marriage and gender differ from the U.S. government’s and those who affirm LGBTQ expressions of marriage and gender.

Restoring Religious Freedom’s Reputation

Such an approach could also help reestablish a positive perception of religious freedom, which has diminished in recent years in large part because of the struggle around LGBTQ rights. For too many, “religious freedom” is simply code for discrimination.

In actuality, religious freedom is a fence, not a hammer. Religious freedom protects us from government imposition on our religious beliefs and practices. It does not impose our religious beliefs on others through law. Religious freedom, when applied properly, is a sacred American value, and if we do not reclaim it, the results in coming decades could have negative consequences far beyond the current intersection with LGBTQ rights.

A recent example of a negative view of religious freedom came from the New York Times editorial board. In 2016, the board criticized a long-standing policy at two outdoor pools creating women-only swimming hours a few times a week; this small allowance at two of the city’s many pools provides swimming access primarily for Orthodox Jewish and Muslim women, whose religious beliefs do not allow them to swim with men. Instead of celebrating this policy as one that helps the city respect religious and ethnic diversity – values normally celebrated by the New York Times – the editorial board criticized it as an unacceptable inconvenience for men.

This kind of thinking fails to recognize the underlying value of religious accommodations, allowing all people to live according to their religious beliefs without being relegated to cloisters or compounds or being penalized by the state. And without a model of some positive example of religious rights intersecting with rights for others, it is hard to foresee a future that is positive for religious freedom. In the last five years alone, the Pew Research Center has found that the number of millennials who say churches and religious organizations contribute positively to society has dropped by 25 percent.

Fairness for All is an attempt to create this positive example. It is an attempt to show that religious persons are not against others having rights. Rather, they are for religious persons being able to retain their religious beliefs and practices while still engaging fully in the public square. There are currently too few examples of people being for religious freedom without being against someone else’s rights – hence our current impasse.

Common Questions

Disagreement is not unexpected even among supporters of religious freedom who share the same goal. As we have discussed Fairness for All with leaders across the country, there are some common questions that have been asked.

Should SOGI rights be codified?

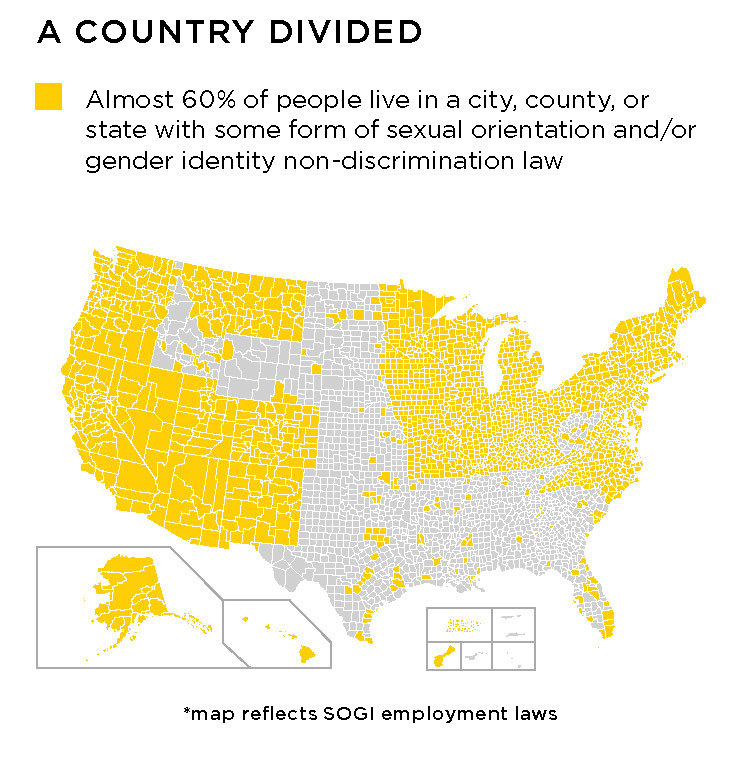

First, sexual orientation and gender identity rights (SOGI) are already codified extensively. Nearly 60 percent of Americans live in states, cities, or counties where some form of SOGI protection exists, and 100 percent of Americans live in a country where same-sex marriage is a right under the Constitution.

In other words, SOGI rights already exist in law. Federal legislation is the last area where they are not, but our federal courts are moving in that direction. Most recently, in April 2017 an en banc panel of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the protections for sex contained in the Civil Rights Act include sexual orientation, and multiple judges around the country have concluded the same about gender identity.

Certainly, the Constitution requires that SOGI rights be balanced against religious rights, so the question becomes: Would we prefer that Congress create this balance through law, or should we just rely on the First Amendment and leave it to the courts?

Gene Schaerr, a Supreme Court litigator and law professor at Brigham Young University’s law school, researched how religious freedom fared when the courts interpreted a right embedded in a law passed by Congress versus when they interpreted a right based solely in the First Amendment itself. He found that since 1986 religious freedom consistently fares much better when explicitly protected in a statute. Under Chief Justice William Rehnquist, the Supreme Court heard 11 private religiously motivated conduct cases between 1986 and 2005. Six of the seven that had a statute for the Court to rely on were decided in favor of religious freedom (86%), while only two of the four that relied on the First Amendment favored religious freedom (50%). Similarly, under Chief Justice John Roberts, the Supreme Court has heard seven such cases thus far. Where there is a statute, religious rights have prevailed five out of five times (100%). However, only one of two First Amendment cases have prevailed (50%).

In other words, when the courts must make a decision, having sound legislation affirming our religious liberties makes those liberties more likely to prevail.

Will the religious freedom protections hold?

Even if balanced legislation is created, will the courts chip away at the religious protections? Generally, courts are predisposed against overturning legislation; unless it’s blatantly unconstitutional, courts prefer to defer to the will of the people and their representatives. As the statistics above show, if the religious freedom protections in Fairness for All were challenged in the Courts, they would have a very strong likelihood of being upheld.

In addition, University of Illinois law professor Robin Fretwell Wilson, a leading First Amendment scholar, recently surveyed how often religious freedom protections in law were overturned by legislatures. She could find only one example: The Illinois state legislature overrode a state religious freedom law in order to expand O’Hare International Airport. The precedent thus far is that once legislative balances are struck, they tend to last, and the courts tend to uphold them.

But won’t the law be sending the wrong message?

Some believe that the law follows culture; others believe the law serves a pedagogical function and teaches. If in fact the law does educate, what should it teach? Is the law where we should seek good theological teaching about sexuality and marriage? Or in a pluralistic democracy, where the law is not supposed to privilege one religion over another (or secularism over religion), is it not a better role for the law to teach that people with different views can live together peaceably and to ensure that churches and other faith-based organizations can live out their theological convictions without compromise?

In fact, Fairness for All is not a statement on marriage or sexual conduct. While Obergefell addressed same-sex marriage, Fairness for All simply addresses access to basic areas of public space such as employment, housing, and financial credit. While there are religious beliefs about marriage that intersect with how these play out (hence the need for religious exemptions), the legislation itself is not commenting on marriage or sexuality. Rather, it only says that all people should have access to these basic public areas.

Could the legislation even pass?

Is there too much water under the bridge for such a positive, pro-active approach to succeed? While it is true that trying to do this work is like growing a garden where a nuclear bomb has been dropped, Fairness for All remains the most politically viable path forward.

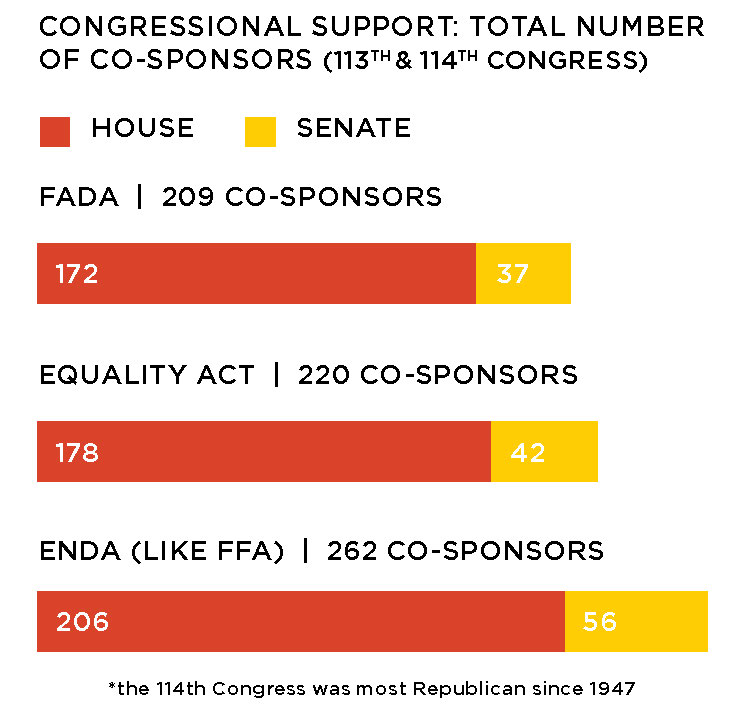

In the 114th Congress, which had a Republican majority and in fact was the most Republican Congress since 1947, the First Amendment Defense Act had fewer total co-sponsors (209) than the Equality Act (220). The Employment Non-Discrimination Act (a balanced approach most like Fairness for All) had the most support, with 262 co-sponsors in 2013. These numbers indicate that protecting LGBTQ rights over religious freedom have slightly more support (even in a Republican Congress) than stand-alone religious rights, but they also indicate that a both/and approach gains the most political support.

The flurry of legislative and court activity around these issues shows that there is a need for Congress to act swiftly. Though no state has passed LGBTQ rights laws since 2009, the number of cities, counties, or towns with such protections has risen from 171 to 336. This year, Ohio and Pennsylvania will both be taking up LGBTQ rights bills. The Trump administration has indicated support for both pro-LGBTQ rights and pro-religious rights. All of this indicates that this is the perfect time for Congress – specifically Republicans acting from a position of strength – to secure religious liberties into the future.

Will this legislation equate sexual orientation and race in the law?

Putting SOGI rights into the Civil Rights Act itself does not equate SOGI with race under the law. In addition to race, the Civil Rights Act protects people from being discriminated against based on sex, national origin, age, pregnancy, disability, or religion – yet the law treats each differently. The fact that they are all in the same law doesn’t make them the same as each other. Whether or not there are exceptions is a key difference: There are almost no exceptions for race, but there are more exceptions for other categories. Since there would be a number of religious exemptions in the Fairness for All legislation, it would make SOGI rights more like these latter categories than race.

How may this impact the future?

None of us knows the future, of course. But we explore this seeking to be faithful to what we are called to do: to love God and love our neighbors; to seek the good of our cities; to turn the other cheek; to go two miles if we’re forced to go one. And we know we’re called to be faithful to the mission of the Christian institutions where we work. Fairness for All seeks to allow us to both love our neighbor and preserve the mission of our institutions so that they can contribute to the good of the city, state, and country they are located in. And we hope that by not just fighting for ourselves, but by also using our political power and privilege to stand up for the rights of our LGBTQ neighbors, loved ones, brothers, and sisters, we can help reclaim the Gospel’s witness, reminding all citizens – including those holding views different from ours – that Christ and the good news he brought are for everyone.

Shapri D. LoMaglio is the vice president for government & external relations at the CCCU. A native of Tucson, Ariz., LoMaglio is a graduate of Gordon College and of the University of Arizona’s James E. Rogers College of Law.