Magazine

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters. Genesis 1:1–2 (RSV)

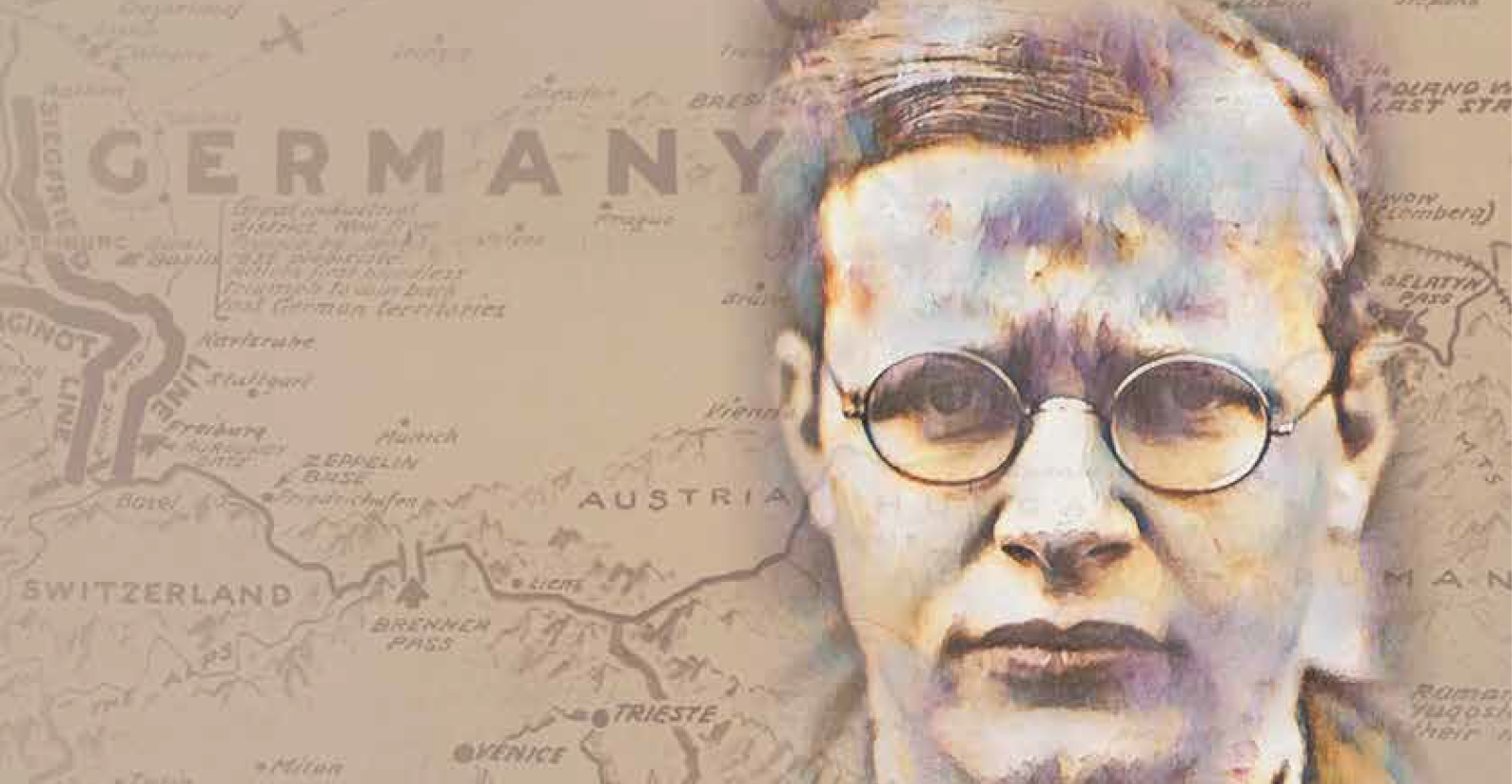

Inspired by Karl Barth’s determination to break with the historical-critical efforts of the age, Dietrich Bonhoeffer turned to Genesis 1–4:1 for a lecture series in the winter 1932–1933 semester as a source for theological understanding concerning how Christians could live at any point in time between Eden and the Apocalypse, but, in particular, during what was proving to be an anxious season. To their credit, the students who heard Bonhoeffer offer those lectures that semester insisted he publish them in Creation and Fall. If they had not done so, we may never have known what he offered during those unsettling days as the Third Reich rose to power.

Central to what Bonhoeffer offered that semester, and for our focus on how Christian colleges can plan for the world in which they find themselves, is Bonhoeffer’s opening claim: “The church of Christ witnesses to the end of all things.” Such a claim is eschatological in that it focuses our eyes on the end of history and how one day all things will find their ultimate fulfillment in Christ. As a result, the church “views the creation from Christ; or better, in the fallen, old world it believes in the world of the new creation, the new world of the beginning and the end, because it believes in Christ and nothing else.” The church, and all other institutions to which she gives birth (such as a Christian college), in turn, claim to serve in her name, focus their sight by properly appreciating “the witness of Holy Scripture.” Individuals draw inspiration from their study of Scripture, but “the Bible is after all nothing other than the book of the church.” As Christ’s body, the church bears witness to the end — that all things will find their fulfillment in Christ on the day of Christ’s return.

While living in the anxious middle, that end informs how we understand God’s abiding relationship with our predecessors, with us, and those who may follow us. When understood properly, such an understanding does not provide a means of escape for the church and a Christian college to which the church gives birth; rather, it provides a means of understanding how to discern the paradoxical reality in which a Christian college finds itself — how to thrive in a world in which it ultimately does not belong.

As a result, Bonhoeffer contends that any reading of Genesis 1–4:1, a reading of the very beginning, must begin by understanding “the end of our whole world.” Debates concerning the historical and literary merits of Genesis 1–4:1 have their place. The story of creation, however, “must be read in a way that begins with Christ and only then moves to him as its goal.” Such a claim may not register as being radical in nature until one compares it to the state of biblical scholarship during Bonhoeffer’s time and, in many ways, our own today. What currently presents as biblical scholarship, for example, is often captive to the competing stories of myriad individuals instead of being found in the magnanimous story of Jesus Christ — a story that knows its end, properly sees its beginning, and defines the present regardless of how great or small the challenges.

One way to assess the value of plans proposed by Christian colleges is to inquire about the size of the stories that animate them. Does that story, often more implicit than explicit, yet nonetheless always present, reflect an appreciation for the end Christ alone ushers into existence? Or does that story reflect an appreciation for something smaller or, dare we say, petty? One way of discerning the difference between the two is by considering how much time is spent on such a plan or in meetings detailing the qualities that do not define an institution compared to detailing the qualities that do.

The size of that story determines the size of an imagination. Small stories yield contradistinctive details. Large stories may eventually yield contra-distinctive details but only as derivatives of distinctive details. The story Christ ushers into existence defines those distinctive details. Or, in the case of a Christian college, to what end should it aspire to order its efforts?

When drawing upon Creation and Fall as a means of understanding to what end a Christian college should aspire to order its efforts, we propose that Bonhoeffer makes at least three points that merit consideration. First, while seemingly evident, Bonhoeffer challenges us to remember that God alone is God and that upon such an understanding all subsequent theological convictions find their proper place. “In the beginning — God” may be the most critical words in all of Scripture if for no other reason than no one could testify to the beginning other than God and God alone.

For Bonhoeffer, “God is the absolute beginning or the primal reality, who had being before our life and thinking, with all its anxiety. God alone tells us that God is in the beginning.” We can know of the beginning but by no means of our own. By various means of revelation, God testifies to the beginning, something that, again, God alone can do. Bonhoeffer would then go on to contend, “We can know of the beginning in the true sense only by hearing of the beginning while we ourselves are in the middle, between the beginning and the end.” Hearing, as we do in Scripture, is not the result of human speculation. By faith, hearing is an acceptance of the most fundamental condition of reality — God exists. God alone existed at the beginning, and what we know of God’s existence is the result of God’s revelation.

For Bonhoeffer, such a claim concerning God is not simply the result of ensuring that the most basic tenet of historic Christian orthodoxy be properly placed. The underlying challenge is that communities charged with the cultivation of created potential often wrestle with the malady of practical atheism more than almost any other set of institutions to which the church gives birth. Such a challenge lurks in questions we rarely pause to consider; nevertheless, it defines the pace of our days, the source of the talents we bear, and the truths we propose. Bonhoeffer belabors the points that God exists, that God alone existed at the beginning, and that what we know of God’s existence is the result of God’s creation as a means of confirming our radical dependence upon God. A properly ordered existence demands we never delude ourselves into thinking, however subtle the temptation, that we are God. Bonhoeffer would have nothing of such thinking in the winter of 1932–1933, nor should we as we navigate the anxious middle in which we currently find ourselves. The root conviction any Christian college must set before itself when planning for its future is that God exists.

Second, human beings, as with all creation, are God’s creation. For Bonhoeffer, being God’s creation demands we appreciate “that in the beginning God created.” As humans, we cannot step outside of ourselves — out of the middle in which we find ourselves — and in and by ourselves define the beginning. This beginning, the beginning in which God alone existed, “is distinguished by something utterly unique — unique not in the sense of a number that one can count back to, but in a qualitative sense, that is, in the sense that it simply cannot be repeated, that it is completely free.” All of creation, including the presence of humanity, is the result of God’s nature as creator.

Part of what makes us as human beings unique among all of creation is our ability to reflect God’s nature. Regardless, we are incapable of creating out of nothing. With God, Bonhoeffer argues, “There is simply nothing that provides [God with] the ground for creation. Creation comes out of this nothing. God affirms the nothing only to the extent that God has already overcome it.” Humans create, but humans create out of something, the something that God created in its origin and to which proper appreciation is due.

For Bonhoeffer, this understanding is not simply affirmed in the opening words to Genesis but made possible to comprehend in full in the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Bonhoeffer goes so far as to offer that, absent a proper Christology, we cannot understand the full theological significance of God’s ability to create out of nothing.

To Bonhoeffer, “the dead Jesus Christ of Good Friday and the resurrected Lord of Easter Sunday [reflect] creation out of nothing, creation from the beginning.” Failure to appreciate the theological significance of Christ’s death and resurrection means humanity is incapable of appreciating what it means: “In the beginning — that is, out of freedom, out of nothing — God created heaven and earth.” Such an understanding proves critical to understanding how God relates to creation and thus serves as the foundation for how creation relates to God.

Third, only when we acknowledge that God alone is God and that God alone created out of nothing do we as human beings begin to understand what it means to be disciples — people who, by God’s grace, participate in rightly ordered relationships with God and, in turn, with one another. In making this claim, Bonhoeffer confirms once again that “the creation still rests entirely in God’s hands, in God’s power; it has no being of its own.” Only then, however, can he go on to claim, “the praise of the Creator is completed only when the creature receives its own being from God and praises God’s being by its own being.”

In the first two verses of Genesis 1, Bonhoeffer sees the imprint of the relationship the Creator desired to have with creation and, in turn, what kind of relationship creation was called to share with the Creator. Apart from the Creator, creation has no being or even essence of its very existence. All that is present in creation is ultimately dependent upon the Creator. By the nature of its existence, creation is called to praise the Creator — such is its very purpose.

The relationship that creation and the Creator share, however, is not complete according to Bonhoeffer until it “praises God by its own being.” As asked and answered in the Westminster Shorter Catechism:

Q: What is the chief end of man?

A: Man’s chief end is to glorify God and to enjoy him forever.

As with all creation, we find our being in God. Our being, however, finds its completion when we praise God as an expression of our own being.

The question then is, what role does a Christian college play in the lives of the individuals it serves? Is its chief end or aspiration, in whatever ways that aspiration may be exemplified, “to glorify God and to enjoy him forever”? Or do other aspirations, aspirations parading as distinctively Christian, define that aspiration? At the heart of any planning process, a Christian college is called by its very nature — or, borrowing from Bonhoeffer’s terminology, being — to root its efforts in a clear understanding of discipleship whether the locale in which that understanding of discipleship is exercised is its library, laboratory, studio, recital hall, residence hall, or athletic field. Only when such an aspiration is clear and collectively embraced is the social imagination that gives life to a Christian college fully realized.

Adapted from The Anxious Middle: Planning for the Future of the Christian College by Todd C. Ream and Jerry Pattengale. Copyright © Baylor University Press, 2023. Reprinted by arrangement with Baylor University Press. All rights reserved.

Todd C. Ream is professor of humanities, executive director of faculty research and scholarship, and senior fellow at the Lumen Research Institute at Indiana Wesleyan University (Marion, IN). He also serves as the CCCU’s senior fellow for public engagement. Jerry Pattengale is university professor and the co-founder and co-director of the Lumen Research Institute at Indiana Wesleyan University (Marion, IN).