Magazine

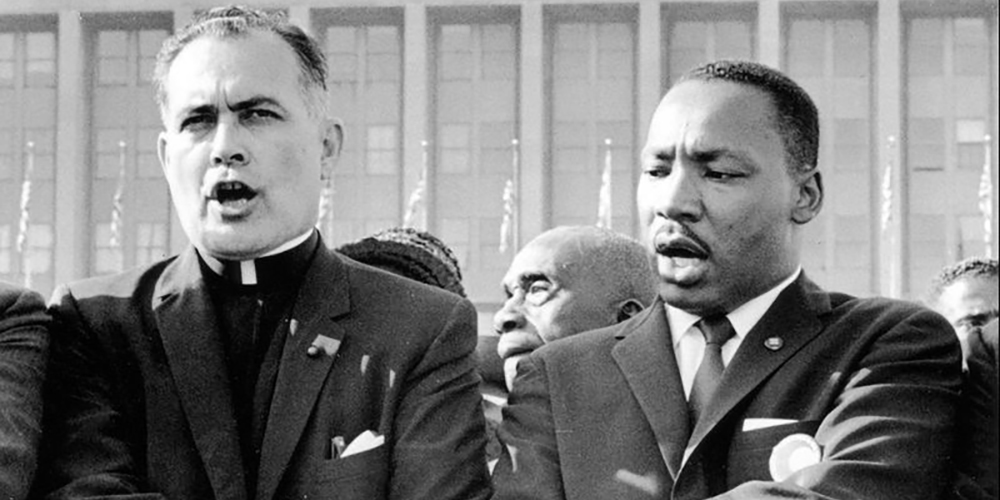

Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. (1917-2015), is considered by many to have been one of the twentieth century’s greatest university presidents. His tenure as president of the University of Notre Dame lasted 35 years (1952-1987), arching across tumultuous periods such as the late 1960s and early 1970s. Highlights of his time leading Notre Dame include doubling enrollment and drastically increasing the university’s endowment, student aid, and average faculty salary.

During his presidency, Hesburgh also served as a national leader, accepting appointments from the White House to serve on the National Science Board, the Civil Rights Commission, the Clemency Board, the Select Commission on Immigrant and Refugee Policy, and from the Vatican to serve as its delegate to the International Atomic Energy Agency. In recognition of his efforts, Hesburgh received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Medal of Honor, a record-setting 150 honorary doctorates, and was one of two individuals (the other being John F. Kennedy) the United States Postal Service placed on a stamp in 2017.

Jointly published in the spring 2021 issue of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities’ Update, the following excerpt is from Todd C. Ream’s Hesburgh of Notre Dame: The Church’s Public Intellectual. While the book offers insights into Hesburgh’s record of service, its primary focus is on Hesburgh’s theological understanding of his identity and, in turn, the service he offered.

The following excerpt explores how Hesburgh understood his calling as a champion for civil rights. As Christian college and university leaders continue to contend with the legacy of racism, Hesburgh’s perspective on prejudice is just as relevant and important today as it was when he was Notre Dame’s president serving on the Civil Rights Commission.

Defining Prejudice

In the foreword for Charles Y. and Ellen Siegelman’s edited volume Prejudice, U.S.A., Hesburgh offered details concerning why he, as a priest, one called to mediate between the eternal and the temporal, was called to wrestle with prejudice and equality. According to Hesburgh, “There is perhaps no quality of human life that lends itself more to self-delusion than prejudice.” Too often, people think they can define prejudice, recognize it when they see it, and, of course, are free of it themselves. In contrast, Hesburgh argued, “No one really wants to be prejudiced, but almost everyone is prejudiced, and only the honest person will admit it, reluctantly and without pride.”

Hesburgh made what some may view as a sweeping claim in relation to prejudice — that the finite condition plaguing humanity compels individuals to make rash judgments or claim they know more than they do. Theologically, Hesburgh argued that “fundamentally, this means passing judgement, normally detrimental or negative, on some one or some group, without sufficient evidence to justify the judgment — hence rash judgment.” Prejudice is thus problematic on its own. However, Hesburgh’s deeper concern was “what makes prejudice so spiritually dangerous is the rashness and irrationality of all that it brings in its train: fear, suspicion, dislike, disdain, revulsion, hatred — all unfounded, and all leading inevitably and irrationally to discrimination, social disunity, and the denial of human dignity.” If one were to follow prejudice where it all too often leads, Hesburgh believed it compromised the image of God — the source of human dignity — present in all human beings. Prejudice is thus “not only faulty, but also inflexible judgment, characterized more by emotion than reason,” paving a path to various vices.

In Hesburgh’s estimation, prejudice and the vices it perpetuated took place on two levels. First, prejudice exists on a personal level and influences relationships. In this regard, Hesburgh said, “Prejudice is best described as the poison of personal relations, the most divisive element of our society, the most corrosive element of our human nature, since it goes against our reason and falsifies our judgments of other persons, makes us and others the prey of irrational fears and hostilities.” Essentially, prejudice drives us to live out of our fears, see others as threats, and maintain our advantage over them. Prejudice compels us to succumb to simplistic or objectified views of others for the sake of our own comfort.

Prejudice, however, did not exist only on a personal but also on a societal level. According to Hesburgh, prejudice “becomes an integral part of a religion, race, nationality, color, or ultimately, culture. Prejudice in this sense gets passed on to all members of society or culture, in the family, in the neighborhood, in the school, even alas, in the church.” Prejudice and the social vices it perpetuates are transmitted among members in a particular group at a particular time and from one group in time to the group poised to succeed it. As a result, Hesburgh claimed, “In a very real sense, to divest ourselves and our future generations from prejudice will require profound cultural change in our attitudes, a change from within.”

Toward the end of the draft of his foreword for Prejudice, U.S.A., Hesburgh began to envision how the personal and societal levels of prejudice could be combatted. Although he identified the Church’s guilt for perpetuating prejudice, he also saw it as an essential part of the solution. Hesburgh thus called upon the educative capacities of the Church to address this challenge when he noted:

It all begins with education — preachment if you will, but this is just a beginning. Today, more than ever before, the word must be joined to the act, an act of all religious persons in the local community, working together to end prejudice and the fruits of prejudice. There is no limit to the scope of this collaboration for justice and charity and social unity and peace.

According to Hesburgh, the Church was not only commissioned to be a voice for human relations that defied prejudice and the vices it perpetuated; it was also uniquely organized to do so. The catholic, or universal, nature of the Church transcended the lines — such as race and nationality — along which prejudice was often drawn.

Hesburgh believed the Church at its core was defined by a peculiar anthropology, “one of equal spiritual dignity before God and men, a dignity that must be respected and buttressed by the same love by which God loves us and we Him.” That anthropology was defined by at least two components that animated all of Hesburgh’s subsequent views concerning civil and human rights and the mediating role he was called to fulfill.

First, such an understanding goes all the way back to the first chapter of Genesis, particularly verses 26–27:

Then God said: Let us make human beings in our image, after our likeness. Let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and birds of the air, the tame animals, all the wild animals, and all the creatures that crawl on the earth. God created mankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.

By Genesis 3, details become available concerning the depravity that would also define human beings. Regardless, human beings were created in God’s image, bear God’s image, and thus in Hesburgh’s estimation, are defined by an anthropology that defied prejudice.

Second, the anthropology Hesburgh noted was defined by relations God shared with human beings and human beings were, in turn, called to share with one another. Hesburgh turned to the words Christ offered in response to a question from a scribe concerning the greatest of all commandments:

The first is this, “Hear, O Israel! The Lord our God is Lord alone! You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength.” The second is this: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” There is no other commandment greater than these. (Mark 12:29–31)

Hesburgh claimed that this Christian anthropology compelled him to believe all people “are equal as children of God, Our Father; all human beings have equal dignity and an equal eternal destiny; despite the differences of talent or grace, all deserve our interest, understanding, and help, especially the least brethren.”

As his career with the Civil Rights Commission progressed, these two components of his Christian anthropology defined in various ways how he served as a mediator between the eternal and the temporal, between the oppressed and their oppressors.

Todd C. Ream serves on the higher education and honors faculties at Taylor University, as a fellow with the Lumen Research Institute, and as the publisher for Christian Scholar’s Review. The author and editor of numerous books, this book is the first in a series Ream is preparing on Hesburgh’s life and legacy.